Ed. note: This post is part of the Spotlight on Commerce series highlighting the contributions of current and past members of the Department of Commerce during Women's History Month.

The U.S. Census Bureau has always been ahead of the curve when it comes to employing women. Ever since 1880, when it started using professional enumerators rather than U.S. marshals, the Census Office had employed women in that role. With the advent of the Hollerith tabulating machine in 1890, women moved into the role of keypunchers. By 1909, 10 years before the 19th Amendment granted national women's suffrage, over 50 percent of the Census Bureau’s 624 employees were women. As women proved themselves as capable as the men, and with the increasing number of women in the workforce, it became harder for the Census Bureau to justify assigning all supervisory positions to men. By 1920, the Census Bureau would once again push forward by appointing the first five female supervisors, as well as the first three female expert chiefs of divisions.

Mary Capitola Oursler was born in May of 1872 in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. Mary was the oldest of Anna and John Oursler’s four children, only three of whom would reach maturity. John Oursler was the first man from Westmoreland County to enlist during the Civil War. He stayed in the state militia afterwards and eventually rose to the rank of colonel. He and his brother, Jacob, also ran a marble cutting business. Their work included producing eight of the monuments at the Gettysburg Battlefield. Around the turn of the century, John left the family business, for which Mary briefly worked, and moved his family to Washington, D.C. for federal employment in the revenue department.;

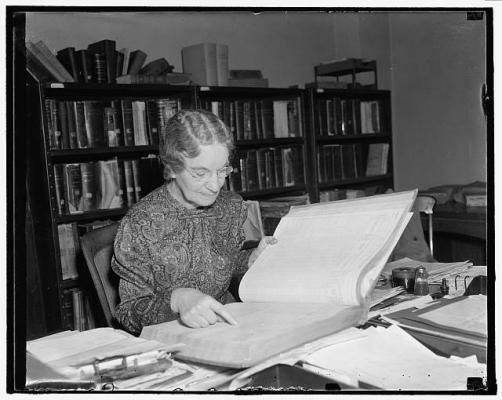

Mary came with her family to Washington around 1900 and began working for the Census Office that year. By 1901, she was working as a clerk. In 1908, Mary moved up to records maintenance clerk and eventually became the Official Custodian of Records. From here, Mary would maintain the original census returns for the entirety of the United States for over 30 years. In this position, Mary safeguarded what she believed was “the greatest human document in the country,” something especially important after a 1921 fire destroyed the 1890 records. Part of this responsibility revolved around the Census’ commitment to privacy — when a journalist interviewing her in 1930 started poking around in a random 1910 return, Mary curtly ordered him to desist. In 1930, the Census Bureau’s standard for releasing individual census information to the public was 50-60 years. In 1952, an agreement between the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA - established in 1934 to house official records) and the Census Bureau extended the wait to 72 years with NARA responsible for the release. They later codified this agreement in U.S.C. Title 44.

Mary’s job as the warden of the nation’s census schedules included helping people to facilitate their use, particularly for age verification, as many states had not issued birth certificates. During her tenure, an estimated 500 people came to see Mary every month. She also received a large amount of mail, sometimes as much as 3,500 letters a day. The requests ranged from ascertaining nationality or age for work or travel within the United States to genealogical requests to prove citizenship or inheritance. As global hostilities heated up in the late 1930s and 1940s, Mary estimated that 100,000 people a year came just to verify their ages so they could work in war industries that required draft registration based on age. Mary also aided American citizens abroad wishing to return, but who had no proof of citizenship other than through their family's census data. From 1909 until her retirement in 1941, Mary was the gatekeeper for all of these requests. Just a year later, the Census Bureau transferred all Census Records to NARA.

Throughout her career, Mary worked with a large variety of social clubs, many of which focused on American genealogy. Mary was a member of the National Genealogical Society, serving as a librarian, a registrar, and a member of the executive committee. Mary was also deeply involved with the Daughters of the American Revolution and through that role was able to preserve more than 150 volumes of valuable genealogical data slated for destruction. She was a charter member of the Daughters of American Colonists; the director of Huguenot Society of Washington in 1930; chair member of the Daughters of the War of 1812; and a member of the Descendants of the Barons of Runnymede, multiple state historical societies, the League of Republican Women, and many others. In her retirement from the Census Bureau, Mary worked closely with the Red Cross during the upheaval of World War II.

In the latest publically available census, 1940, Mary lived with her sister and brother-in-law, Edith and George Shoemaker, in Washington, D.C. Thanks in part to the strict policies practiced by Mary, the time limit on viewing the 1950 Census, the last census to count her, will not expire until April 1, 2022. Mary never married and, after suffering a heart attack in 1955, she moved back to Latrobe, PA to be near her brother, James. She passed away on February 17, 1956, at the age of 83. Mary’s service to her country was a benefit to all Americans, and an inspiration for the women that followed.

This blog was originally published as part of the U.S. Census Bureau's series spotlighting influential women during Women's History Month.